1993-1994 Imagitec

Platforms: Atari Falcon and Jaguar, Sega Mega CD, Amiga CD 32 and PC

As we moved into the 1990s, games were becoming far bigger and bolder – especially with emerging new data storage options for consoles and computers. Space Junk was to be an ambitious title by Imagitec, who were asked by Atari to produce a space adventure game for their new Falcon platform. We pull together information from various press sources from the time about the game and try to piece together a little of what it was about, and what happened in the end.

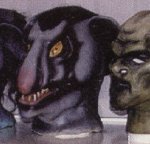

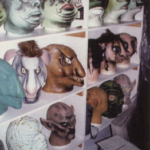

Due originally for release back in June 1993, the game was to feature over 200 locations with digitised backdrops, between 60-100 fully animated characters and each complete with speech samples. What made this game quite uncommon at the time was the use of puppets/masks to create the characters and animations – giving an almost life-like feel to the game. Certainly the digitisation would require some decent storage capacity, meaning it had to be CD for storage – otherwise the Falcon version would require a mega-ton of floppy disks or at least a cut down edition produced.

Although it seemed to be lined up initially as an exclusive for the Falcon, Imagitec decided to hedge their bets on more than one platform (which would turn out to be wise). They would add the new Sega Mega CD to the line up early on when discussing the game with Sega Force magazine in 1993.

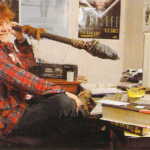

Lead designer on the project was Nigel (Pig) Kershaw, with Dawn Whitehead-Binns creating plaster heads and sculptures for the game. Shelagh Pickford would be busy painting the latex masks and sorting out costumes, and Marie Fox + Sharon Dunsford were tasked with producing background work and characters using airbrush and gouache paint (later scanned to PC). Shaun McClure also worked as an artist on the game, though it is unknown in what capacity, and it is likely that other artists were also chipping in too at various stages.

Nigel came up with the idea of Space Junk specifically to make use of puppets in a game. He also didn’t like the idea of using clay models for animating, and wanted to avoid that route completely. The team of artists would create characters in latex rubber, animate and then digitise – a process they named “Imagimation”. Filming would occur at a studio just down the road from Imagitec.

The process would start off with everything initially storyboarded, before being constructed for real for the game. When Dawn had managed to get a plasticine/plaster representation of a head from their process, it would be sent off to Soft Options, who were famous for making the Spitting Image puppets. They would create latex and foam based masks for the actors to wear when animated and digitised into the game.

The “actors” were mostly just the Imagitec team acting out particular sequences and roles to be digitised into the game. Over time, Imagitec had an entire room full of latex masks and other creatures intended for use within the game. It was quite something for a team which had nowhere near the resources of a company such as LucasFilm doing similar things. Head of Imagitec, Martin Hooley, once told us that Space Junk was an exceptional concept and well before its time. The team doing ground breaking experimental stuff, especially when considering they were just a Yorkshire indie studio.

Most of the design would come from imaginations within the team, with inspiration from books, films and comics of the time. One of the biggest inspirations it seems would be the UK comedy Red Dwarf, with Space Junk aiming to feature similar humour and style throughout. The game itself would also aim to have the feel of classic Lucasfilm/Lucasarts SCUMM adventures, but with realistic graphics and other styles of game play (such as 3D flight sequences) blended in at different points of the story.

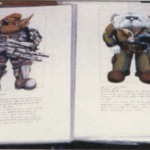

So what of the game’s story itself? The rough plot detailed in magazines indicated that you were a space pilot, a spaced-out dog called Randolf, who travels around the galaxy hauling other people’s “junk” with your partner – The Righteous Dub. A collision strands you on a planet, where you must try and escape, rescue your partner and complete a series of jobs, trades and tasks. Everything is set in the world of the Federation galaxy, populated with strange creatures where corruption is rife.

One Atari magazine had also the following blurb to describe more of the back story: “The Federation is on its knees, crippled by social upheaval and financial recession. It is a chaotic time, a time when men of low moral fibre, little integrity and nauseating skin complaints can make a fortune. In other times, they may have been called smugglers, pirates, thugs, mobsters, bandits, hoodlums or traffic wardens, but now they all go by the moniker of … Space Junk.”

The main protagonist Randolf would be moved around the landscape by clicking onto different areas, interacting with different objects and characters. Characters would include Droogs, Snaggers, Slurges and Squinks for example. You could choose actions and interact with the game by using a SCUMM-like menu system, but with more an icon-based approach. When you would interact with a particular character, the game would switch to an animated sequence featuring the digitised latex puppets and various options to speak to them.

There would also be some 3D polygon space sim sections to break up the adventure parts as you travelled to different planets, as well as a number of sub games, where you could play cards against creatures, play arcade machines in a bar or gamble in a casino for example. Many of these sounded like ideas just on paper initially. According to Sega Force, the game was going to be huge, with many character confrontations and path choices, making for an epic sounding title.

In addition to the artists, Ian Howe was likely to have been musician for the game, composing some powerful soundtracks and effects to be included throughout the game. Retro Gamer magazine revealed that Julian Aiden-Salter was one of the main developers on the game originally – his last game before leaving Imagitec in 1992. He had talked of writing some polygon flight sequences, along with the adventure parts. After Julian had left, both Andrew Seed and Nigel Conroy would take over development duties – further trying to progress the game as much as possible. It is likely that there were other developers working on the game too throughout it’s lifespan.

Over the space of a year or so, the game would feature a fair bit within the press, with preview screenshots, photos of the masks/process and features that talked to Imagitec about the game. Some of these press bits and pieces you can see here. A preview of the game running was also apparently shown on Gamesmaster/Games World, but we couldn’t find the episode in question. It may have shown scenes that we haven’t shown here, possibly from an earlier/later build. Please do get in touch if you happen to know which episode/s it was in.

Unfortunately, the amount of work involved with the production of masks and digitisation had been heavily underestimated, resulting in delays. The mask and costume process was very time consuming and costly overall, and there was a mountain of work still to be done. Many character sequences still needed to be filmed, and many backgrounds and part of the game story had to be completed and digitized up. Platform changing disruptions over time also wouldn’t help the cause…

Space Junk went way past its planned June 1993 release date – by which point the Atari Falcon hadn’t really taken off at all. After poor sales/general support of the Atari Falcon, it was reported by French magazine Joystick in November 1993 that Imagitec decided to move the game onto other platforms. Work continued on the Mega CD version, with a lot of compromises due to the limited palette and other platform limitations.

One of the platforms to be moved onto was the Atari Jaguar, which seemed a natural progression from the Falcon, but wasn’t without its challenges as the team got used to its new and interesting architecture. By this time, it was also reported that Space Junk was going to be released on the Amiga CD32 platform, as well as PC (due for release in February 1994). Exclusivity had seemingly gone completely out of the window by this stage. However, it was never to be in the end, and the game just completely disappeared – never appearing on any platform at all.

A musician working on Freelancer 2120 at the time (which also didn’t see release) recalls that when he joined Imagitec to work on that project, there was no work going on at all on Space Junk. It had already halted. All the latex masks though were still in the office. So what happened?

Martin Hooley in later years would suggest that the game was completely cancelled after it became clear that that Atari Jaguar CD was going to flop and that they wouldn’t get their investment back. Oddly, Director of Software Development John Skruch would mention Space Junk in an internal Jaguar Release schedule document dated February 1995 in a “Pending Titles and Agreements” list, saying there was no contract or script for the game supplied at that stage. So was it therefore killed off early by Imagitec when they saw how things were panning out for Atari and it’s Jaguar platform, and therefore never fully signed up with them at all?

The Mega CD and Amiga CD32 versions were likely canned for similar reasons of platform failure, though this hasn’t been completely confirmed. It does seem odd though that from the massive investment already made, the PC version wasn’t kept going (or even that the PlayStation or Saturn wasn’t brought into play). It suggests that maybe there were other issues overall and it wasn’t just the failure of the Jaguar which caused the game’s cancellation. Perhaps with Space Junk, it was just becoming too costly to keep going, and was felt better to kill it than potentially let the game bankrupt them. The project by this stage had already been going for just over 2 years now, and there was still a lot of work left to do. Maybe there are other reasons yet to surface.

Andrew Seed would give a few recollections about the development on AtariAge. “For a few months I worked on Dino Dudes , Freddy ( Nigel Conroy) worked on Raiden and Trev did a Falcon dsp mod player. We stopped for a week or so to get the Space Junk demo updated.” he began. “Originally Space Junk was going to be released on CD but as nobody had them then it decided to be on floppies :( . The demo itself came on multiple discs so i would dread how many disc it would have been on.

Sometime later we were shown the Jaguar in a pc case running Minter demos which looked impressive and then Freddy and myself were moved onto the Jaguar. I had completed the majority of the game so another programmer whose name I forget took over the Falcon version. A year or so later i was asked to remove the password protection which was easy so that it could be released as shareware.”

It is hoped that something of the game could be found and shared in the future. We assume that some of the original masks and assets still exist (and are believed to be in the ownership still of some of the artists), so hopefully we may be able to get some photos of them someday to add to the site. As for actual builds of the game, thankfully you can experience a bit of the Atari Falcon version which is out there to download.

Things are not so fortunate for the Amiga CD32, PC, Atari Jaguar or Sega Mega CD versions at present, with nothing yet to have surfaced. It isn’t fully known if the CD32 and Jaguar versions were ever actually started, though we believe that PC and Mega CD versions were. Sega Force even suggested that they saw the Mega CD version in action, but it could well have just been the Falcon version, with them being told it would essentially be the same with less colours.

Could Space Junk have been truly a ground breaking title? Sadly we will never know.

Credits:

Thank you to Ross Sillifant for many of the scans provided and bits of information located on the game over the years, with many scans from archive.org. Also to Pirate Dragon for the video clip highlight below, Atarimania.com for some of the Falcon emulated screenshots we have included and Karl Kuras for one of the extra scans (via archive.org).

Here’s the espisode of Games World that it was featured on, which should have been broadcast 1993-03-02

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FD1ZqHinRwk&t=227s

Thanks Pirate Dragon! I’ll get that linked into the piece now quickly – much appreciated and great to see more of the game in action! :)